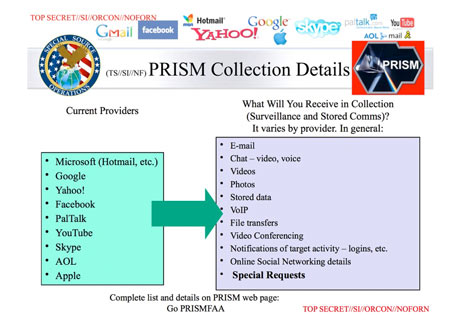

With recent revelations about the U.S. government’s PRISM program targeting top internet companies to monitor online activity, state surveillance is a matter of public discussion. PRISM is an intelligence tool that gathers data from emails, file transfers, images, chats, and search histories. Questions of civil liberties, government overreach, ethics and trust define much of the public discussion. However, the discussion has ignored the massive amount of ongoing corporate surveillance occurring in a different context – one which has no state remedy found in Constitutional law. These discrete surveillance contexts must be addressed from an ethical as well as legal standpoint.

In the ongoing conversation about digital surveillance and privacy, I am hoping to add some critical perspective on the nature of ethics and trust surrounding surveillance based on Helen Nissenbaum’s 2010 book Privacy in Context. My goal is to understand how different surveillance contexts mean different things for individuals in terms of values, morality, and the law. Ultimately, I aspire to suggest a regime of “trust contexts,” operating within the ecosystem of surveillance, to address social power imbalances in a democracy.

Ethical and legal charges about digital invasions of privacy usually surface in response to some apparent surveillance, whether undertaken by governments, corporations, law enforcement, or other agency. Nissenbaum (2010) claims that privacy can be understood within a structure of “contextual integrity” in which streams of personal data, originating in different social contexts, are handled by entrenched socio-legal conventions. These conventions may be violated by the monitoring practices associated with information technologies; thus contextual integrity is broken. Privacy violations, then, are judged in accordance with the goals and values of a specific context. For the purposes of this conversation, contexts include information privacy in medical environments; transactional privacy in consumer environments; security and encryption. As an example, we expect medical information to be transparent to our insurance companies but not to our neighbors. We expect our online retail transactions to be transparent only to the companies with which we engage. But in some cases, so-called “breaches” of data may be difficult to decipher – for example, what norms govern search data? How private is it? To what extent is search data subject to legal evidentiary norms?

Nissenbaum advocates understanding privacy “neither as a right to secrecy nor as a right to control but as a right to appropriate flow of personal information” [p. 127]. I am interested in examining the notion of appropriate flow as it regards information gleaned from surveillance. Clearly, information assembled from Google searches, disassociated from the user, and then bundled with millions of other data subjects to be sold for predictive data modeling differs contextually from RFID chips implanted into a data subject’s body. The latter is much more invasive, and the former is encountered in daily online existence. Grasping these contextual differences is essential to implementing a regime of ethical information practices that can apply across multiple surveillance contexts. For now, Fair Information Practices (FIPs) in Europe and the U.S. tend to ignore surveillance contexts, particularly with regard to ethics.

|

To apply a critical perspective to an understanding of surveillance and contextual integrity, we might begin by considering these questions.

- What are the contexts in which we can expect surveillance?

- What are the contexts in which we allow surveillance?

- How do benign forms of surveillance alter our perceptions of privacy rights?

- What are the implications for human dignity and respect regarding current socio-legal norms?

Understanding surveillance contexts involves close scrutiny of the systems and practices that are implicated in various surveillance contexts. Some of these systems and practices are outlined below in an attempt to ascertain the possibilities for what is involved in surveillance contexts:

- Actors: Corporations, governments, military, institutions (educational, medical, employer), individuals, networks, groups, regulatory agencies. The motivations, powers, and results from these surveillance actors differ greatly. Torin Monahan has argued, for example, that when the government provides the people power to identify terrorists, it promulgates a culture of fear and an acceptance of loss of privacy rather than a feeling of security. However, individuals surveil themselves and their friends on social media with less regard for privacy or security implications.

- Activities: Data collection, watching, recording, reporting, compilation (aggregation, distribution). These activities are subsumed within the same FIPs policies regardless of their divergent natures and consequences.

- Power structures: Surveillance as safeguarding, collection, intrusion, tracking, discrimination, exclusion, blackmail. Clearly, these power contexts imply their own legal and ethical frameworks.

- Internal values: Goals, ends, or purposes include safety, crime fighting, documentation, profit, control, hacking, transparency, self promotion, social justice. How do these values govern what might be considered an “appropriate flow” of information gathered from surveillance? Most governments recognize the social value of surveillance for the purposes of crime abatement, but what constitutes an appropriate flow of information derived from hacking? From self promotion?

The norms of surveillance differ, expectations differ, power relations differ, and appropriate flow differs – all according to surveillance context. Whether or not a society permits or disdains particular surveillance contexts shapes notions of appropriateness. In the following [non-exhaustive] list of contexts, society allows surveillance:

- Security contexts

- Social networking – keeping friendly “tabs”

- Lifeguards at the beach

- Store loyalty cards

- Population census

- Medical oversight

- Journalism’s watchdog function

- Reality TV

- Self surveillance

- Sousveillance

These are types of benign surveillance in which no sinister character is assumed. Such a benign context has its own norms – that it won’t be abused, that it is used only for purposes of communal good, and that the only privacy invasion happens when someone “has something to hide.” Thus, there is an expectation of trust that the benevolent surveillance context won’t be abused. This expectation of trust fosters a perception that information flows from these benign contexts are indeed appropriate. Perhaps, then, legal notions of privacy are inapplicable to benign surveillance contexts if no legal harm is present.

In the following [non-exhaustive] list of contexts, society disdains surveillance:

- Excessive CCTV

- Social networking – stalking

- RFID tagging – tracking

- Smart phone malware (such as PlaceRaider)

- Intrusion by corporate, law enforcement, or government authorities

- Data mining – misuse of records, data for discrimination, exposure, profit or illegality

These contexts often have to do with creepiness (an assault to dignity) or with unscrupulous dissemination practices. These contexts show a norm of exposure which is perpetuated by increased and continued visibility. For example, Place Raider is a malicious Android app that hijacks a smart phone’s camera, secretly takes photos, and reconstructs those images into 3D pictures of private locations. Such malevolent surveillance is a context with its own norms – it is intrusive, it exposes things we do not want exposed, it may harm us financially or in terms of discrimination, and it is often used in concert with capitalist profit imperatives. There is little trust expectation in these contexts. Hence the expectation of untrustworthiness fosters a perception that information flows from these malevolent contexts are not appropriate. Individual data protection schemes arise from malevolent surveillance contexts and are embedded in some of the assumptions governing privacy solutions in Europe and the U.S.

When thinking about appropriate information flows, surveillance contexts, and notions of ethics and trust, we must distinguish the legal dimensions of privacy law from the social dimensions. Within a legal dimension, we ask how surveillance contexts adapt to technological change and evolving norms. Is privacy about control or about appropriate flow of information? Is there a role for trust in privacy law? Are surveillance contexts associated with legal dimensions of privacy law always malevolent? Clearly, surveillance modes that enforce rules and norms show that power relations condition the contexts of privacy. For example, as Nissenbaum notes, surveillance practices are often justified simply by virtue of novelty – social norms have changed around the collection of data for the purposes of aggregation to create consumer behavior models. And executives of social networking sites argue “we have so many users that like us – what other proof do you need that norms have changed?” This means that privacy itself is commodified as corporations establish the extent to which intrusions on individual privacy are profitable. Ordinary people are not privy to the machinations of the various algorithms, storage tactics, and dissemination devices that surveillers use, and thus power imbalances are evident. U.S. legal regimes claim privacy as a fundamental value, but the practices of unregulated markets weaken that value. Moreover, concepts of ethics and trust are often outside the legal conversation about privacy systems.

From a social perspective, however, privacy is about human dignity. It is a common good, equated with freedom and identity. While legal privacy remedies operate at the individual level, privacy itself is a collective social value. It is a core human value that equals a boundary between self and other – a protective barrier from public intrusion. Again, a power dynamic enabled by surveillance conditions our notions of privacy whereby accepted notions of privacy are increasingly reworked. For example, social networking sites like Facebook operate as corporate technologies that enable personal expression despite ever-present surveillance. The boundaries between private individual and public citizen become blurred in these environments. In the face of many surveillance contexts, privacy exists as both a commodity and a common good. Thus, there is confusion among capitalist imperatives, control of personal information, personal identity, and the democratic nature of an open internet. How can we deny the ethical implications of this confusion?

Ultimately, if we ignore contexts of surveillance we devalue privacy, and we devalue ethics. To interrogate privacy concerns, contexts of surveillance must be addressed situationally (e.g., benign vs. malevolent) in terms of ethics and democracy. For example, privacy opponents argue that we need surveillance to catch wrongdoers while privacy advocates argue that surveillance harms individuals. How do these contexts differ? What good is being served? What interests are being weighed? Is trust being violated? What power imbalances are evident? What technical regimes are implicated? How is information being used?

These questions also frame a consideration of what “appropriate” flow of information means. The “products” of surveillance are in some way mediated by power dictates, profit motives, legal rights, and human dignity. When Anonymizer, the company behind anonymous web browsing, co-created a global surveillance system (called TrapWire) that it sold to several governments, the breach of trust became news.

Invasions of privacy are cheap, useful, and profitable. I am recommending that surveillance, privacy, democracy, the public good, and ethics be linked in public conversation. Surveillance activities must be assessed ethically in terms of the mode, context, and conditions of data collection and use.

We must consider capitalist imperatives that drive surveillance, control of personal information, and the purported democratic nature of socio-technological systems. FIPs doctrine is insensitive to trust violations and to the ethical dilemmas inherent in particular techniques of information extraction that might cross sensitive boundaries. Perhaps implant technologies cross those boundaries to represent an inappropriate flow of private information. Perhaps the sheer amount of information gleaned about us daily creates a narrative that represents an inappropriate flow of private information. These considerations will help the development of an environment of trust that considers the ethical nature of information flow resulting from various surveillance contexts.

In benevolent surveillance contexts, trust expectations are high that information gleaned from surveillance preserves human dignity and operates for public good. In malevolent surveillance contexts, trust expectations are lower – that information will be used for profit, illegal means, discrimination, or social power imbalances. Kant’s categorical imperative is applicable to an understanding of trust in different surveillance contexts – it merges the politics and ethics of trust in ways that illuminate justice (Myskja, 2008). Information regulations provide a context within which various actors can behave in trustworthy ways since laws allow everyone to practice their own ideas of the common good. From a policy perspective, a violation of social trust through deception or the failure to honor data collection agreements results in a devaluing of community and the common good. So, socio-technical policy regimes must develop contextual trust responses to surveillance uses and abuses. Fair information practices (FIPs) currently operate as a set of principles governing the collection/use of data about individuals. The five FIP principles are: (1) notice/awareness; (2) choice/consent; (3) access/participation; (4) security; and (5) enforcement. These can be reworked to account for different levels of trust in accordance with Kantian ethical principles of respect for the common good and for human dignity. Trust is based on a cycle of risk and action as complementary elements. In benign surveillance contexts, information flows may be trusted because of low risks to personal privacy with rewards to the common good in the form of security or safety. In malevolent surveillance contexts, information flows are not trusted due to high risk of privacy violations with vague understandings of potential rewards (either for common good or, more likely, for corporate profit). Expansion of FIP principles to include respect for a data-self-identity set apart from a personal-self-identity can establish trust contexts for respective surveillance contexts. FIP principles can include an ethical “score” of sorts for businesses and governments with transparent policies that create value without also creating harm or injustice.

The PRISM program lacks such transparency, as do nearly all corporate surveillance campaigns. We have no knowledge of how governments and corporations are constructing our “data selves,” and this fact militates against trust, civil liberties, and a general ethical sensibility. We have reason for suspicion when, in such a malevolent surveillance context, we have no assurance that data will not be abused. Public culture and the common good will be served when trust is increased by policies respecting boundaries of the personal self apart from profit motive and other unethical capitalist or state imperatives.

References:

Nissenbaum, H. (2010). Privacy in context: Technology, policy and the integrity of social life. Stanford, CA: Stanford Law Books.

Monahan, T. (2006). Surveillance and Security: Technological Politics and Power in Everyday Life. New York: Routledge.

Myskja, B.K. (2008). The categorical imperative and the ethics of trust. Ethics and Information Technology,10, 213–220.