Venturing again into an example I do not know enough about, I wanted to recommend this Wired article on how the comics industry has been managing the shift to digital formats and distribution. The title, “The iPad Could Revolutionize the Comic Book Biz — or Destroy It” is deeply misleading, a predictable gloss from a magazine that has long trafficked in technological determinism. But the body of the article quietly goes about understanding the comic book industry in a much more nuanced way, refusing to frame this change as either sermon or eulogy. The key move, crucial to avoiding these traps, and so rare not just in the press but even in talk from information industries themselves, is to recognize that the audience is not homogenous, that they will not all live or die by print or by digital. The move to digital formats and distribution, while not inevitable, has clear economic momentum, but this does not mean that the only choices for “comic book fans” (as a homogenous block) are migration or exodus.

Venturing again into an example I do not know enough about, I wanted to recommend this Wired article on how the comics industry has been managing the shift to digital formats and distribution. The title, “The iPad Could Revolutionize the Comic Book Biz — or Destroy It” is deeply misleading, a predictable gloss from a magazine that has long trafficked in technological determinism. But the body of the article quietly goes about understanding the comic book industry in a much more nuanced way, refusing to frame this change as either sermon or eulogy. The key move, crucial to avoiding these traps, and so rare not just in the press but even in talk from information industries themselves, is to recognize that the audience is not homogenous, that they will not all live or die by print or by digital. The move to digital formats and distribution, while not inevitable, has clear economic momentum, but this does not mean that the only choices for “comic book fans” (as a homogenous block) are migration or exodus.

The article notes that, as independent comics publishers (here “independent” means not Marvel or DC) experiment with digital forms, particularly on tablets like the iPad, not only might this convince some collectors to migrate to digital, but more importantly it could reach “lapsed fans,” those who have dabbled in an interest in comics in the past but did not become regular buyers. Digital versions could reach an audience that the print form does not. Pulling these readers back into the fold (no pun intended), industry optimists suggest, might actually expand the readership for comics, smooth the way for digital form comics, while not immediately eating into sales at brick-and-mortar stores. Traditional fans raised on visiting the local store, having the paper copies in hand, and lovingly storing them in slipcovers, will for a while need to continue to have this form, suggesting that the transition to digital need not be total or instant. The article also notes the surprising power of vendors, who can still exact vengeance on a publisher who is too eager to privilege the digital, and the oversized influence of the two giants in the field, Marvel and DC, who can invest in digital formats without worrying about that blowback, and without bringing independents along with them.

Much of this may be wishful thinking, naive predictions designed to believe that the comics industry can prosper even as newspapers and magazines struggle. It could be dead wrong in its prognostications. And the lessons here may not hold for other industries. The reason I highlight this piece is that, too often, discussion of culture industries in transition fail to tell a complex story of what the industry already was. They fail to notice how different parts of the industry, the market, or the form itself will or could respond differently to emerging digital venues. They often fail to understand why the transition to digital is rarely a night-to-day switchover, that digital and print (or digital and analog, or online and material distribution) are likely to co-exist for some time. The wild overstatements around the transition in music, from the record industry, from Napster, from fans, from Apple, and from bands, were all wildly off the mark: music did not shrivel up and die, lawlessness did not prevail, and creativity was not set free. Yet things did change, and in ways that, when we look back in twenty years may appear almost as momentous as everyone was saying — but not in such simple terms as those claims suggested.

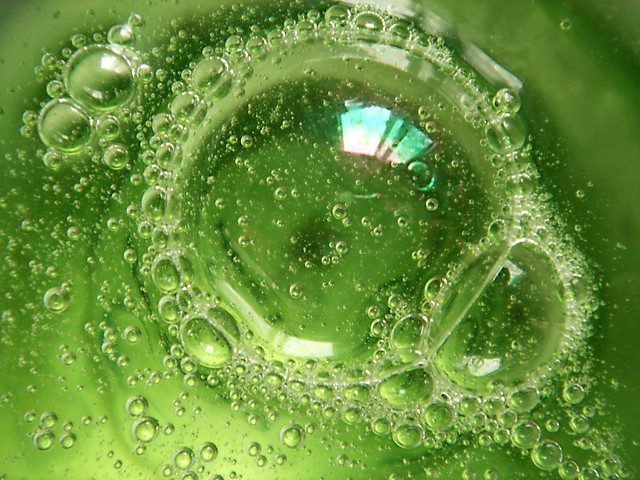

Following Bourdieu, I find it more helpful to think about cultural production as a “field,” with many actors, organizations, and genres nestled together like bubbles in a glass, jostling for space, reaching momentary equilibrium before a new actor or technology or form pushes into the space and everything else has to adjust, re-settle, and sometimes pop. Digital formats and distribution opportunities may be a very large push, or be many little shoves all at once, but it does not wipe the field clean, and the adjustments made in response are myriad, complex, in competing directions, and to some degree unpredictable. It is those adjustments, more than “digital,” that explain what new equilibrium that field of cultural production will find in response.

Following Bourdieu, I find it more helpful to think about cultural production as a “field,” with many actors, organizations, and genres nestled together like bubbles in a glass, jostling for space, reaching momentary equilibrium before a new actor or technology or form pushes into the space and everything else has to adjust, re-settle, and sometimes pop. Digital formats and distribution opportunities may be a very large push, or be many little shoves all at once, but it does not wipe the field clean, and the adjustments made in response are myriad, complex, in competing directions, and to some degree unpredictable. It is those adjustments, more than “digital,” that explain what new equilibrium that field of cultural production will find in response.

The only thing that is notably absent in this article, is the question of how the format and availability of comics affect current and future creators of comics. I suspect that the comic book store and the yearly Comic-con convention in San Diego are important environments that help kids become comic artists, that not only nurture skills but also offer a sense of community and purpose. Digital distribution lacks the lived locations in which comics circulated. On the other hand, they may offer different kinds of social spaces. When we think about digital distribution we too often tend to think about the business of providing culture and the audiences to which it is provided, but the cultivation of amateurs and professionals in the process of culture’s production and distribution must be another important piece of the puzzle.